TACCUINI DI APPUNTI

Questo libro è stato concepito, poi scritto, tutto o in parte, sotto diverse forme, tra il 1924 e il 1929, tra i miei venti e venticinque anni. Quei manoscritti sono stati tutti distrutti. Meritavano di esserlo.

Ritrovata in un volume della corrispondenza di Flaubert, molto letto, molto sottolineato verso il 1927, la frase indimenticabile: «Quando gli dèi non c’erano più e Cristo non ancora, tra Cicerone e Marco Aurelio, c’è stato un momento unico in cui è esistito l’uomo, solo». Avrei trascorso una gran parte della mia vita a cercar di definire, e poi descrivere, quest’uomo solo e, d’altro canto, legato a tutto.

Ripresi i lavori nel 1934. Lunghe indagini. Scritte una quindicina di pagine, ritenute definitive. Progetto ripreso e abbandonato più volte tra il 1934 e il 1937.

Per molto tempo, immaginai il lavoro sotto forma d’una serie di dialoghi, nei quali si sarebbero fatte sentire tutte le voci dell’epoca. Ma, checché facessi, il particolare prevaleva sull’insieme, le parti compromettevano l’equilibrio del tutto. Sotto tutte quelle grida, la voce di Adriano si perdeva. Non riuscivo a dar vita a quel mondo come l’aveva visto e compreso un uomo.

La sola frase rimasta della stesura del 1934: «Incomincio a scorgere il profilo della mia morte». Come un pittore si colloca davanti a un orizzonte e sposta senza posa il cavalletto a destra, poi a sinistra, avevo finalmente trovato il punto di vista del libro.

Prendere un’esistenza nota, compiuta, definita – per quanto possano mai esserlo – dalla Storia, in modo da abbracciarne con un solo sguardo l’intera traiettoria; anzi, meglio, cogliere il momento in cui l’uomo che ha vissuto questa esistenza la pesa, la esamina, e, per un istante, è in grado di giudicarla; fare in modo che egli si trovi di fronte alla propria vita nella stessa posizione di noi.

Mattinate a Villa Adriana; sere innumerevoli trascorse nei piccoli caffè attorno all’Olympieion; andirivieni incessante su i mari della Grecia; strade dell’Asia Minore. Per riuscire a utilizzare questi ricordi, che sono miei, essi hanno dovuto allontanarsi da me quanto il Secondo secolo.

a G.F.

Esperimenti con il tempo: 18 giorni, 18 mesi, 18 anni, 18 secoli. Sopravvivenza immota delle statue che, come la testa dell’Antinoo Mondragone al Louvre, vivono ancora all’interno di quel tempo che non è più. Lo stesso problema considerato in termini di generazioni umane: due dozzine di mani scheletriche, più o meno venticinque vegliardi basterebbero a stabilire un contatto ininterrotto tra Adriano e noi.

Nel 1937, durante un primo soggiorno negli Stati Uniti, feci qualche lettura per questo libro nella Biblioteca dell’Università di Yale. Scrissi la visita al medico e il passo su la rinuncia agli esercizi fisici: frammenti che sussistono, rimaneggiati, nell’edizione attuale.

Comunque, ero troppo giovane. Ci sono libri che non si dovrebbero osare se non dopo i quarant’anni. Prima di questa età, si rischia di sottovalutare l’esistenza delle grandi frontiere naturali che separano, da persona a persona, da secolo a secolo, l’infinita varietà degli esseri o, al contrario, di attribuire un’importanza eccessiva alle semplici divisioni amministrative, agli uffici di dogana, alle garritte delle sentinelle in armi. Mi ci sono voluti questi anni per calcolare esattamente la distanza tra l’imperatore e me.

Sospendo il lavoro di questo libro, tranne qualche giorno a Parigi, tra il 1937 e il 1939.

Il ricordo di T. E. Lawrence ricalca in Asia Minore quello di Adriano; ma lo sfondo di Adriano non è il deserto. Sono le colline di Atene. Più ci pensavo e più la vicenda d’un uomo che rifiuta (e, per prima cosa, si rifiuta) m’invogliava a presentare attraverso Adriano il punto di vista dell’uomo che non rinuncia o che rinuncia qui per accettare altrove. Va da sé, del resto, che in questo caso ascetismo e edonismo su molti punti sono interscambiabili.

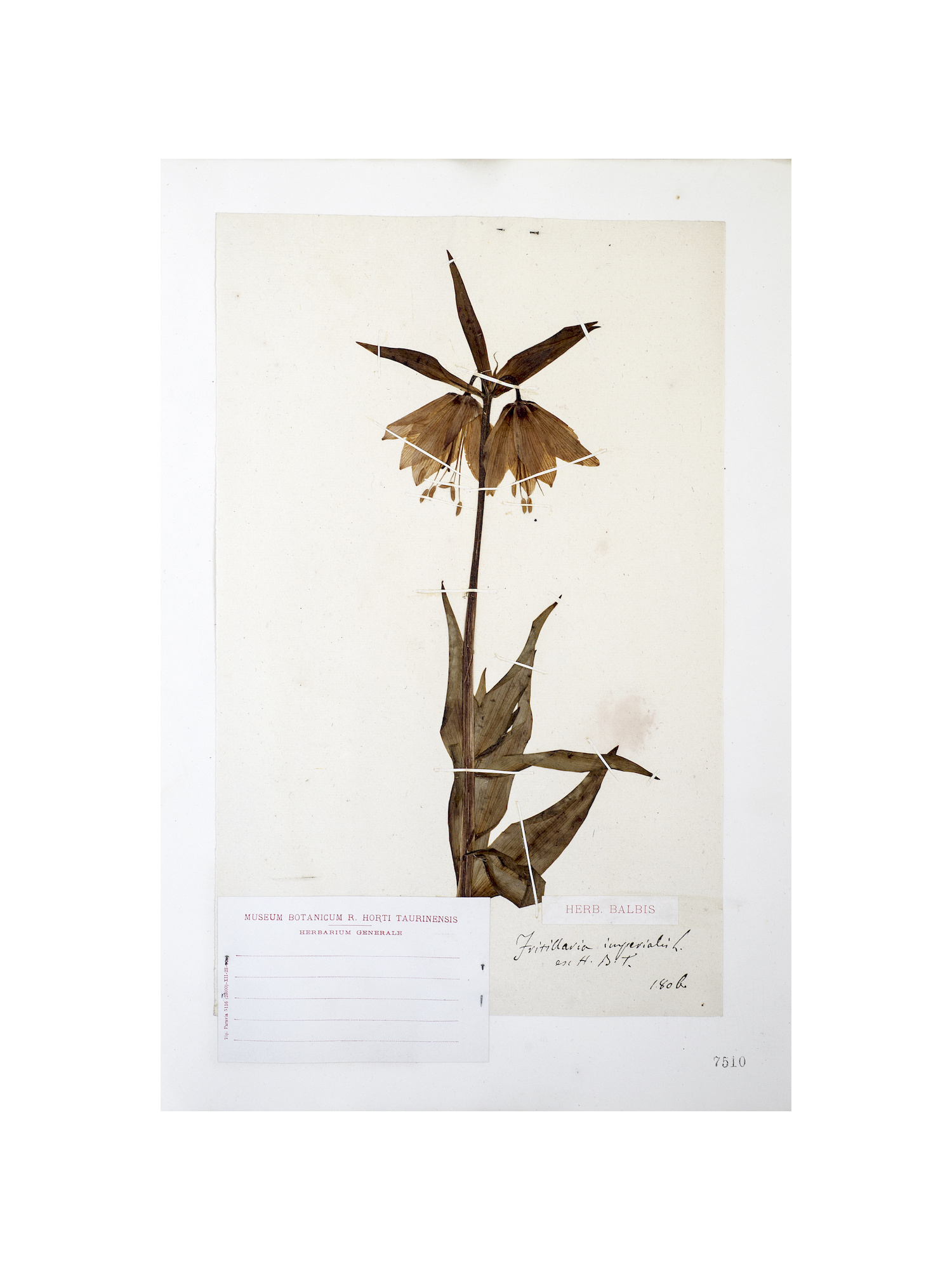

Nel 1939, il manoscritto fu lasciato in Europa con la maggior parte degli appunti. Portai con me tuttavia negli Stati Uniti i riassunti fatti anni prima a Yale, una carta dell’impero romano alla morte di Traiano che mi portavo appresso da anni e il profilo dell’Antinoo del Museo Archeologico di Firenze, che avevo comprato là nel 1926: un profilo giovane, serio, dolce.

Abbandonato il progetto dal 1939 al 1948; ci pensavo a volte, ma con scoraggiamento, quasi con indifferenza, come all’impossibile; e provavo un poco di vergogna, per aver potuto tentare un’impresa simile.

Affondo nella disperazione dello scrittore che non scrive.

Nei momenti peggiori di scoraggiamento e di atonia, andavo a rivedere nel bel Museo di Hartford nel Connecticut una tela romana del Canaletto, il Pantheon bruno e dorato contro il cielo azzurro d’un tardo meriggio d’estate. Tornavo a casa ogni volta rasserenata, riscaldata.

Nel 1941, scoprii per caso in un negozio di colori a New York quattro stampe del Piranesi che G. ed io comprammo. Una di esse, una veduta di Villa Adriana che non conoscevo, rappresenta la cappella del Canopo dove nel Diciassettesimo secolo furono estratti l’Antinoo in stile egizio e le statue delle sacerdotesse in basalto che si vedono oggi al Vaticano: una struttura circolare, esplosa come un cranio; ne pendono disordinatamente rovi simili a ciocche di capelli. Il genio quasi medianico di Piranesi vi ha fiutato l’allucinazione, i lunghi percorsi che la memoria ripercorre, l’architettura tragica del mondo interiore. Per anni ed anni ho guardato quella immagine quasi ogni giorno, senza dedicare un pensiero all’opera iniziata in altri tempi. Credevo di aver rinunciato ad essa. Tali sono i curiosi meandri di quello che chiamano oblio.

Nella primavera del ’47, riordinando delle carte, bruciai gli appunti presi a Yale. Ormai, sembravano definitivamente inutili.

Eppure, il nome di Adriano figura in un saggio sul mito della Grecia che scrissi nel 1943 e Caillois pubblicò in «Les Lettres Françaises» di Buenos Ayres. Nel 1945, l’immagine di Antinoo annegato, quasi fosse trasportata su questa corrente di oblio, risale in superficie, in un saggio ancora inedito “Cantico dell’Anima Libera“, che scrissi alla vigilia d’una grave malattia.

Ripetersi senza tregua che tutto quello che racconto qui è falsato da quello che non racconto; queste note non circondano che una lacuna. Non vi si parla di ciò che facevo in quegli anni difficili, dei pensieri, i lavori, le angosce, le gioie, né dell’immensa ripercussione degli avvenimenti esteriori e della perenne prova di sé alla pietra di paragone dei fatti. Passo altresì sotto silenzio le esperienze della malattia e altre più segrete che queste portano con sé; e la perpetua presenza o ricerca dell’amore.

Non importa. Ci voleva forse quella soluzione di continuità, quella frattura, quella notte dell’anima che tanti di noi hanno provato, ciascuno a suo modo, in quegli anni, e spesso in modo ben più tragico e definitivo di me, per costringermi al tentativo di colmare non solo la distanza che mi separava da Adriano, ma soprattutto quella che mi separava da me stessa.

Utilità di ciò che si fa per se stessi, senza alcun pensiero di profitto; durante quegli anni di straniamento, avevo continuato a leggere gli autori antichi: i volumi dell’edizione Loeb-Heinemann, con le loro copertine rosse e verdi, erano diventati una patria per me.

Uno dei modi migliori per far rivivere il pensiero d’un uomo: ricostituire la sua biblioteca. Già da anni, senza saperlo, avevo lavorato a ripopolare gli scaffali di Tivoli. Non mi restava più che immaginare le mani gonfie d’un malato mentre svolge i rotoli manoscritti.

Rifare dall’interno quello che gli archeologi del Diciannovesimo secolo hanno rifatto dall’esterno.

Nel dicembre del 1948, ricevetti dalla Svizzera – dove l’avevo depositata durante la guerra – una valigia piena di carte di famiglia e lettere di dieci anni prima.

Sedetti accanto al fuoco per venire a capo di quella sorte di orribile inventario post mortem. Trascorsi così tutta sola parecchie sere. Aprivo pacchi di lettere prima di distruggerle, scorrevo quel mucchio di corrispondenza con persone dimenticate e che mi avevano dimenticato; alcuni vivevano ancora, altri erano morti. Alcuni di quei fogli portavano la data della generazione precedente la mia; persino i nomi non mi dicevano più nulla.

Gettavo macchinalmente nel fuoco quello scambio di pensieri morti con delle Marie, dei Franceschi, dei Paoli scomparsi.

Aprii quattro o cinque fogli dattiloscritti; la carta era ingiallita. Lessi l’intestazione: «Mio caro Marco…» Di quale amico, di quale amante, di quale lontano parente si trattava? Non ricordavo quel nome.

Mi ci volle qualche momento perché mi tornasse alla mente che Marco stava per Marco Aurelio e che avevo sotto gli occhi un frammento del manoscritto perduto.

Da quel momento, per me non si trattò che di scrivere questo libro, a qualunque costo.

Quella notte, riaprii due volumi, tra quelli che mi erano stati resi anch’essi; frammenti di una biblioteca dispersa: Dione Cassio nella bella stampa di Henri Estienne e un volume d’una edizione comune della “Historia Augusta“; le due fonti principali della vita di Adriano.

Li avevo comprati nel periodo in cui mi proponevo di scrivere questo libro.

Tutto quello che il mondo ed io avevamo attraversato nell’intervallo arricchiva quelle cronache d’un’epoca lontana, proiettava su quell’esistenza imperiale altre luci, altre ombre; allora, avevo pensato soprattutto al letterato, al viaggiatore, al poeta, all’amante. Nessuno di questi tratti si cancellava. Ma per la prima volta scorgevo delinearsi con estrema limpidezza, tra tutte quelle figure, la più ufficiale, che era, al tempo stesso, la più segreta, quella dell’imperatore.

L’esser vissuta in un mondo in disfacimento mi aveva fatto capire l’importanza del Princeps.

Mi sono divertita a fare e rifare questo ritratto d’un uomo quasi saggio.

Solo un’altra figura storica mi ha tentato con insistenza quasi eguale: Omar Khayyam, poeta astronomo; ma la vita di Khayyam è quella del contemplatore e dello spregiatore puro; il mondo dell’azione gli è troppo estraneo. E d’altro canto non ho mai visitato la Persia e non conosco la lingua.

Impossibile anche prendere per figura centrale un personaggio femminile; porre, ad esempio, come asse del racconto, anziché Adriano, Plotina. La vita delle donne è troppo limitata o troppo segreta. Se una donna parla di sé, il primo rimprovero che le si farà è di non esser più una donna. E’ già abbastanza difficile far proferire qualche verità a un uomo.

Partii per Taos, nel Nuovo Messico. Portavo con me le pagine bianche su le quali ricominciare il libro, come un nuotatore che si getta nell’acqua senza sapere se raggiungerà la riva opposta.

Lavorai a notte tarda tra New York e Chicago, chiusa nella cabina del vagone letto come in un ipogeo. Poi, per tutto il giorno seguente, nel ristorante d’una stazione di Chicago, dove aspettavo un treno bloccato da una bufera di neve; e poi ancora, fino all’alba, sola nella vettura dell’Espresso di Santa Fé: tutt’attorno, i dossi neri delle montagne del Colorado e l’eterno disegno degli astri.

I brani su l’alimentazione, l’amore, il sonno e la conoscenza dell’uomo li buttai giù così, di getto. Non ho ricordo d’una giornata più fervida, di notti più lucide.

Passo più rapidamente possibile su tre anni di ricerche, che interessano solo gli specialisti, e su l’elaborazione d’un metodo di delirio che può interessare soltanto i folli. E poi, questa ultima parola sa troppo di romanticismo; parliamo piuttosto d’una partecipazione costante, la più chiaroveggente possibile, a ciò che fu.

Un piede nell’erudizione, l’altro nella magia; o più esattamente, e senza metafora, in quella “magia simpatica” che consiste nel trasferirsi con il pensiero nell’interiorità d’un altro.

Ritratto di una voce. Se ho voluto scrivere queste memorie di Adriano in prima persona è per fare a meno il più possibile di qualsiasi intermediario, compresa me stessa. Adriano era in grado di parlare della sua vita in modo più fermo, più sottile di come avrei saputo farlo io.

Chi colloca il romanzo storico in una categoria a parte dimentica che il romanziere si limita a interpretare, valendosi di procedimenti del suo tempo, un certo numero di fatti passati, di ricordi, coscienti o no, personali o no che sono tessuti della stessa materia della storia. “Guerra e pace“, tutta l’opera di Proust, che cosa sono se non la ricostruzione d’un passato perduto? Il romanzo storico dell’800 sconfina nel melodramma e nel racconto di cappa e spada, è vero; ma non più che la sublime “Duchesse de Langeais” e la straordinaria “Fille aux yeux d’or“. Nel ricostruire minuziosamente il palazzo di Amilcare, Flaubert si serve di centinaia di particolari minimi e con lo stesso metodo procede per Yonville. Ai tempi nostri, il romanzo storico, o quello che per comodità si vuol chiamare così, non può essere che immerso in un tempo ritrovato: la presa di possesso d’un mondo interiore.

Il tempo non c’entra per nulla. Mi ha sempre sorpreso che i miei contemporanei, convinti d’aver conquistato e trasformato lo spazio, ignorino che si può restringere a proprio piacimento la distanza dei secoli.

Tutto ci sfugge. Tutti. Anche noi stessi. La vita di mio padre la conosco meno di quella di Adriano. La mia stessa esistenza, se dovessi raccontarla per iscritto, la ricostruirei dall’esterno, a fatica, come se fosse quella d’un altro. Dovrei andar in cerca di lettere, di ricordi d’altre persone, per fermare le mie vaghe memorie. Sono sempre mura crollate, zone d’ombra.

Fare in modo che le lacune dei nostri testi, per quel che concerne la vita di Adriano, coincidano con quelle che potevano essere le sue stesse dimenticanze.

Il che non significa affatto, come si dice troppo spesso, che la verità storica sia sempre e totalmente inafferrabile; accade della verità storica né più né meno come di tutte le altre: ci si sbaglia, PIU’ O MENO.

Le regole del gioco: imparare tutto, leggere tutto, informarsi di tutto e, al tempo stesso, applicare al proprio fine gli esercizi di Ignazio di Loyola o il metodo dell’asceta indù, che si estenua anni ed anni per metter a fuoco con maggior precisione l’immagine che ha creato sotto le palpebre chiuse.

Attraverso migliaia di schede, perseguire l’attualità dei fatti, cercar di rendere a quei volti marmorei la loro mobilità, l’agilità della cosa viva. Quando due testi, due affermazioni, due idee si contrappongono, divertirsi a conciliarle anziché annullarle una attraverso l’altra; ravvisare in esse due aspetti, due stadi successivi dello stesso fatto, una realtà convincente appunto perché complessa, umana perché multipla.

Sforzarsi di leggere un testo del Secondo secolo con occhi, anima, sensi del Secondo secolo; immergerlo in quell’acqua madre che sono i fatti contemporanei; eliminare finché è possibile tutte le idee, i sentimenti che si sono accumulati, strato su strato, tra quegli esseri e noi; e, al tempo stesso, servirsi con prudenza, o soltanto a titolo di studi preparatori, della possibilità di accostare e ritagliare prospettive nuove, elaborate poco a poco attraverso tanti secoli e tanti avvenimenti che ci separano da quel testo, da quell’avvenimento, da quel personaggio. Utilizzarli, in certo modo, come altrettante tappe su la via del ritorno verso un punto particolare del tempo; imporsi d’ignorare le ombre che vi si sono proiettate successivamente, non permettere che la superfice dello specchio sia appannata dal vapore d’un alito, prendere come punto di contatto con quegli uomini soltanto ciò che c’è di più duraturo, di più essenziale in noi, sia nelle emozioni dei sensi sia nelle operazioni dello spirito: anche loro, come noi, sgranocchiarono olive, bevvero vino, si impiastricciarono le dita di miele, lottarono contro il vento pungente, contro la pioggia accecante, l’estate cercarono l’ombra di un platano, gioirono, pensarono, invecchiarono, morirono.

Ho sottoposto più volte a dei medici per una diagnosi i brani brevi delle cronache riguardanti la malattia di Adriano: in fin dei conti, non divergono molto dalle descrizioni cliniche della morte di Balzac.

Per capire di più, ho utilizzato un mal di cuore incipiente.

Chi è Ecuba per lui? si chiede Amleto davanti al guitto che piange su Ecuba. Ed ecco, Amleto costretto a riconoscere che quel commediante che versa lacrime vere è riuscito a stabilire con quella donna morta da tre millenni un contatto più profondo del suo con il padre, sepolto il giorno avanti; egli non soffre abbastanza della sua morte da esser capace di vendicarlo senza indugio.

La sostanza, la struttura dell’essere umano non muta: non c’è cosa più stabile che la curva di una caviglia, il posto d’un tendine, la forma di un alluce. Ma ci sono epoche in cui la calzatura deforma meno: nel secolo di cui parlo siamo ancora molto vicini alla libera verità del piede nudo.

Quando ho fatto formulare da Adriano le sue previsioni sul futuro, mi sono tenuta nel campo del plausibile; a patto, tuttavia, che quei pronostici restassero vaghi. Chi analizza le cose umane senza parzialità in genere non si sbaglia di molto sull’andamento futuro degli avvenimenti; ma commette errori su errori se si tratta di prevedere il modo come si svolgeranno i particolari, le deviazioni: Napoleone a Sant’Elena annunciava che un secolo dopo la sua morte l’Europa sarebbe stata o rivoluzionaria o cosacca; poneva con molta esattezza i due termini del problema, ma non poteva immaginare che si sarebbero sovrapposti uno all’altro.

In genere, ci si rifiuta di scorgere sotto il presente i lineamenti delle epoche future, per orgoglio, per ignoranza volgare, per viltà. Gli spiriti liberi – i saggi del mondo antico – pensavano in termini di fisica o di fisiologia, come facciamo noi; prendevano in considerazione la possibilità della scomparsa dell’uomo, la morte della terra. Plutarco, Marco Aurelio non ignoravano affatto che gli dèi e le civiltà passano, muoiono; non siamo soli a guardare in faccia un avvenire inesorabile.

La chiaroveggenza che ho attribuito ad Adriano non era d’altra parte che una maniera di mettere in risalto l’elemento quasi faustiano del personaggio, quale trapela, ad esempio, nei Canti Sibillini, negli scritti di Elio Aristide e nel ritratto di Adriano vecchio tracciato da Frontone. A torto o a ragione, quando era vicino a morire gli furono attribuite doti più che umane.

Se quest’uomo non avesse conservato la pace nel mondo e rinnovato l’economia dell’impero, le sue gioie, le sue sventure mi interesserebbero meno.

Non ci si dedica mai abbastanza a quel gioco appassionante che consiste nell’accostare i testi: il poema del Trofeo di Caccia di Tespie, che Adriano consacrò all’Amore e alla Venere Urania «sulle colline dell’Elicona, in riva alla sorgente di Narciso» è dell’autunno 124; nella stessa epoca, l’imperatore passò da Mantinea e Pausania ci informa che fece restaurare il sepolcro di Epaminonda e vi fece incidere un suo poema.

L’iscrizione di Mantinea è perduta; ma il gesto di Adriano forse non acquista tutto il suo valore se non lo mettiamo a confronto con un passo dei “Moralia” di Plutarco, il quale ci dice che Epaminonda fu sepolto in quel luogo tra due giovinetti, uccisi al

suo fianco. Se si accetta la data (123-24) del soggiorno in Asia perché è sotto ogni punto di vista la più plausibile, e confermata dai reperti iconografici, per l’incontro dell’imperatore con Antinoo, quei due poemi farebbero parte di quello che si potrebbe chiamare «il ciclo di Antinoo», ispirati l’uno e l’altro da quella stessa Grecia amorosa ed eroica che Arriano evocò più tardi, dopo la morte del favorito, quando paragonò il giovinetto a Patroclo.

Di alcune figure, si vorrebbe sviluppare il ritratto: Plotina, Sabina, Arriano, Svetonio. Ma Adriano non poteva vederli che di scorcio; lo stesso Antinoo si può vederlo solo per rifrazione, attraverso i ricordi dell’Imperatore, vale a dire con una minuzia appassionata; e qualche errore.

Del temperamento di Antinoo, tutto ciò che si può dire è iscritto nella più piccola delle sue immagini. “Eager and impassionated tenderness, sullen effeminacy“: con il mirabile candore dei poeti, Shelley dice l’essenziale in sei parole, là dove critici d’arte e storici del Diciannovesimo secolo, per la maggior parte, non hanno saputo far altro che effondersi in declamazioni virtuose o idealizzare, perdendosi nel falso e nel vago.

I ritratti di Antinoo: ce n’è molti. Vanno dall’incomparabile al mediocre. Ad onta delle variazioni dovute all’arte dello scultore o all’età del modello, alla differenza tra i ritratti presi dal vero e quelli eseguiti in onore del defunto, sono tutti sconvolgenti per il realismo incredibile della figura, sempre riconoscibile al primo sguardo e tuttavia interpretata in tanti modi, per questo esempio unico nell’antichità, di sopravvivenza, di moltiplicazione nella pietra d’un volto che non era quello d’un uomo di stato o d’un filosofo, ma che fu, semplicemente, amato.

Tra tutte queste immagini, le più belle sono due, le meno conosciute e le sole che rivelano il nome di uno scultore: una è il bassorilievo firmato da Antoniano di Afrodisia, che fu trovato una cinquantina di anni fa in un terreno appartenente a un istituto agronomico, «I Fondi Rustici», e attualmente si trova nella sala del consiglio d’amministrazione. Dato che nessuna guida di Roma ne segnala l’esistenza e la città è stracolma di statue, i turisti la ignorano. L’opera di Antoniano è stata intagliata in un marmo italiano e dunque fu certamente eseguita in Italia, senza alcun dubbio a Roma da questo artista. Forse, si era stabilito nell’Urbe o Adriano l’aveva portato con sé da uno dei suoi viaggi.

La scultura è d’una finezza estrema: i pampini di una vite incorniciano di teneri arabeschi quel viso giovane, malinconicamente chino; non si può fare a meno di pensare alle vendemmie d’una breve esistenza, all’atmosfera opulenta d’una sera d’autunno.

L’opera reca le tracce degli anni trascorsi in una cantina durante l’ultima guerra: il candore del marmo è momentaneamente scomparso sotto le macchie di terra; tre dita della mano sinistra sono state spezzate. Così soffrono gli dèi per la follia degli uomini.

[Le righe qui sopra sono state pubblicate la prima volta sei anni fa; nel frattempo, il bassorilievo di Antoniano è stato acquistato da un banchiere romano, Arturo Osio, un personaggio singolare che avrebbe interessato Stendhal o Balzac. Osio riversa su questo bell’oggetto la stessa sollecitudine che ha per gli animali che tiene liberi in una proprietà a due passi da Roma, e per gli alberi che ha piantati a migliaia nella tenuta di Orbetello. Una virtù rara: «Gli Italiani detestano gli alberi»; lo diceva già Stendhal nel 1828: che cosa direbbe oggi, quando gli speculatori uccidono a furia di iniezioni d’acqua calda i pini a ombrello troppo belli, troppo protetti dalle norme urbanistiche, che li disturbano per edificare i loro formicai? E anche un lusso raro: quanti pochi ricchi animano i loro boschi, le loro praterie di animali in libertà, non per il piacere della caccia, ma per quello di ricostituire una specie di mirabile Eden? l’amore delle statue antiche, questi grandi oggetti pacati, durevoli e, al tempo stesso, fragili, è anch’esso ben raro presso i collezionisti, in questa epoca agitata e senza futuro. Dietro il consiglio di esperti, il nuovo possessore del bassorilievo di Antoniano l’ha sottoposto a una pulitura delicata da parte d’una mano abile. Una frizione lenta e leggera fatta con la punta delle dita ha liberato il marmo dalla ruggine, dalle macchie di muffa ed ha reso alla pietra la sua tenue lucentezza di alabastro e d’avorio].

Il secondo di questi capolavori è l’illustre sardonica che porta il nome di Gemma Marlborough, perché appartenne a quella collezione oggi dispersa. Questa splendida pietra incisa sembrava perduta o ritornata alla terra da più di trent’anni; una vendita pubblica a Londra l’ha riportata alla luce nel 1952; il gusto illuminato d’un grande collezionista, Giorgio Sangiorgi, l’ha riportata a Roma: devo alla sua benevolenza d’aver visto e toccato questo pezzo unico; sull’orlo si legge una firma incompleta; si ritiene, indubbiamente con ragione, che sia quella di Antoniano di Afrodisia. L’artista ha racchiuso quel profilo perfetto nello spazio limitato della sardonica con tale maestria che questo frammento di pietra resta la testimonianza di una grande arte perduta alla stessa stregua d’una statua o d’un bassorilievo. Le proporzioni dell’opera fanno dimenticare le dimensioni dell’oggetto; all’epoca bizantina, il rovescio di questo capolavoro fu immerso in una fusione d’oro purissimo. E’ passato così da un collezionista ignoto a un altro fino a che è segnalata la sua presenza a Venezia, in una importante collezione del Diciassettesimo secolo; il celebre antiquario Gavin Hamilton la acquistò e la portò in Inghilterra, di dove oggi è tornata nel suo punto di partenza, che fu Roma. Di tutti gli oggetti ancora esistenti su la faccia della terra, questo è il solo di cui si possa presumere con qualche fondamento che Adriano l’abbia tenuta nelle sue mani.

Bisogna immergersi nei meandri d’un soggetto per scoprire le cose più semplici e l’interesse letterario più generale. Studiando il personaggio di Flegone, il segretario di Adriano, scoprii che a questa figura dimenticata si deve la prima – e una delle più belle – storie di fantasmi, quella tenebrosa, voluttuosa “Fidanzata di Corinto” che ispirò Goethe e Anatole France in “Noces Corinthiennes“. Con lo stesso impegno e con la stessa curiosità disordinata per tutto ciò che eccede i limiti dell’umano, Flegone scriveva assurde favole di mostri a due teste e di ermafroditi che partoriscono. La conversazione alla mensa imperiale, almeno in certi giorni, si aggirava su questi argomenti.

Coloro che avrebbero preferito un “Diario di Adriano” alle “Memorie di Adriano” dimenticano che un uomo d’azione raramente tiene un diario; più tardi, al fondo d’un periodo di inattività, egli si ricorda, prende nota e, il più delle volte, stupisce.

Se mancasse qualsiasi altro documento, basterebbe la lettera di Arriano all’imperatore Adriano sul periplo del Mar Nero a ricreare nelle sue grandi linee questa figura imperiale: esattezza minuziosa del capo che vuol sapere tutto, interesse per i lavori della pace e della guerra, gusto per le statue somiglianti e ben fatte, passione per i poemi e le leggende d’altri tempi. E poi quel mondo, raro in tutti i tempi e che sparirà completamente dopo Marco Aurelio, in cui, ad onta delle più sottili sfumature di deferenza e di rispetto, il letterato e l’amministratore si rivolgono ancora al principe come a un amico.

C’è tutto: il ritorno malinconico all’ideale della Grecia Antica; allusione discreta agli amori perduti e alle consolazioni mistiche cercate dal superstite; attrattiva dei paesi sconosciuti, dei climi barbari. L’evocazione, così profondamente pre-romantica, delle regioni deserte abitate da uccelli marini fa pensare al mirabile vaso trovato a Villa Adriana nel quale, nel candore di neve del marmo, si dispiega in volo nella più completa solitudine uno stormo di aironi selvatici.

Nota del 1949: più cerco di fare un ritratto somigliante, più m’allontano dal libro e dall’uomo che potrebbe piacere; solo qualche amatore dei destini umani comprenderà.

Oggi il romanzo divora tutte le forme; poco a poco si è costretti a passarci. Questo studio sul destino d’un uomo che si chiamò Adriano nel Diciassettesimo secolo sarebbe stato una tragedia; all’epoca del Rinascimento, un saggio.

Questo libro è il condensato d’un’opera enorme elaborata per me sola. Avevo preso l’abitudine di scrivere ogni notte quasi automaticamente il risultato di queste lunghe visioni provocate, durante le quali mi inserivo nell’intimità d’un altro tempo. Prendevo nota dei minimi gesti, delle parole più insignificanti, delle sfumature più impercettibili; le scene che nel libro attuale sono riassunte in due righe, erano descritte nei minimi particolari, quasi le vedessi al rallentatore; queste specie di resoconti, se li avessi aggiunti gli uni agli altri, avrebbero prodotto un volume di qualche migliaio di pagine. Ma ogni mattina davo alle fiamme il lavoro notturno; scrissi così un grandissimo numero di meditazioni molto astruse e qualche descrizione abbastanza oscena.

L’uomo appassionato di verità, o, se non altro, di esattezza, il più delle volte è in grado di accorgersi, come Pilato, che la verità non è pura. Ne conseguono, mescolate alle affermazioni dirette, alcune esitazioni, sottintesi, deviazioni che uno spirito più convenzionale non avrebbe avuto; in certi momenti, rari peraltro, m’è accaduto persino di sentire che l’imperatore mentiva. In questi casi, bisognava lasciare che mentisse, come noi tutti.

Come sono grossolani quelli che dicono: «Adriano sei tu»; ancor di più lo sono coloro che si meravigliano che si sia scelto un soggetto così remoto e straniero. Lo stregone che si taglia il pollice al momento di evocare le ombre sa che esse obbediranno al suo appello soltanto perché lambiscono il proprio sangue; e sa, o dovrebbe sapere, che le voci che gli parlano sono più sagge e più degne d’attenzione che le sue grida.

Non ho tardato molto ad accorgermi che scrivevo la vita d’un grand’uomo; e di conseguenza, un maggior rispetto della verità, una maggiore attenzione, e, da parte mia, un maggior silenzio.

In un certo senso, ogni vita raccontata è esemplare; si scrive per attaccare o per difendere un sistema del mondo, per definire un metodo che ci è proprio. Ma non è meno vero che le biografie in genere si squalificano per una idealizzazione o una denigrazione a qualunque costo, per particolari esagerati senza fine o prudentemente omessi; anziché comprendere un essere umano, lo si costruisce.

Non perder mai di vista il grafico di una esistenza umana, che non si compone mai, checché si dica, d’una orizzontale e due perpendicolari, ma piuttosto di tre linee sinuose, prolungate all’infinito, ravvicinate e divergenti senza posa: che corrispondono a ciò che un uomo ha creduto di essere, a ciò che ha voluto essere, a ciò che è stato.

Qualunque cosa si faccia, si ricostruisce sempre il monumento a proprio modo; ma è già molto adoperare pietre autentiche.

Ogni essere che ha vissuto l’avventura umana sono io.

Il Secondo secolo m’interessa perchè fu, per un periodo molto lungo, quello degli ultimi uomini liberi; per quel che ci riguarda, siamo già molto lontani da quel tempo.

Il 26 dicembre del 1950, una sera gelida sulle rive dell’Atlantico, nel silenzio quasi polare dell’Isola dei Monti Deserti, negli Stati Uniti, ho cercato di rivivere il caldo soffocante d’un giorno di luglio del 138 a Baia, il peso del lenzuolo su gambe pesanti e stanche, il mormorio quasi impercettibile d’un mare senza marea che di tanto in tanto raggiunge un uomo tutto preso dai rumori della sua agonia. Ho cercato di spingermi fino all’ultimo sorso d’acqua, l’ultimo collasso, l’ultima immagine. L’imperatore non ha più che da morire.

Questo libro non è dedicato a nessuno. Avrebbe dovuto esserlo a G. F.; lo sarebbe stato, se non fosse quasi indecente mettere una dedica personale in testa a un’opera dalla quale volevo, soprattutto, cancellare me stessa. Ma le dediche, anche le più lunghe, sono pur sempre un modo inadeguato e banale di onorare un’amicizia così poco comune. Quando cerco di definire questo bene che mi è stato donato da anni, dico a me stessa che un simile privilegio, benché tanto raro, non può tuttavia essere unico; che a volte deve pur succedere che nell’avventura d’un libro riuscito o nell’esistenza d’uno scrittore fortunato, ci sia stato qualcuno, un poco in disparte, che non lascia passare la frase inesatta o debole che per stanchezza vorremmo lasciare; qualcuno capace di rileggere con noi fino a venti volte, se è necessario, una pagina incerta; qualcuno che va a prendere per noi sugli scaffali delle biblioteche i grossi volumi nei quali forse troveremo ancora una indicazione utile, e si ostina a consultarli ancora quando la stanchezza ce li aveva già fatti richiudere; qualcuno che ci sostiene, ci approva, alle volte ci contraddice; che partecipa con lo stesso fervore alle gioie dell’arte ed a quelle della vita, ai lavori dell’una e dell’altra, mai noiosi e mai facili; e non è né la nostra ombra né il nostro riflesso e nemmeno il nostro complemento, ma se stesso; e ci lascia una libertà divina ma, al tempo stesso, ci costringe ad essere pienamente ciò che siamo. “Hospes comesque“.

Apprendo nel dicembre del 1951 la morte recente dello storico tedesco Wilhelm Weber, nell’aprile del 1952 quella dell’erudito Paul Graindor, i lavori dei quali mi hanno molto servito. In questi giorni ho parlato con due persone, G. B. e J. F., i quali hanno conosciuto a Roma l’incisore Pierre Gusman nell’epoca in cui era intento a disegnare con passione le località della Villa. Sentimento di appartenere a una specie di “Gens Aelia“, di far parte della folla di segretari del grand’uomo e partecipare a quella veglia della guardia imperiale montata da umanisti e poeti, i quali si danno il turno attorno a un grande ricordo. Così si forma, attraverso il tempo, (e accade lo stesso, senza dubbio, degli specialisti di Napoleone, degli innamorati di Dante) una cerchia di spiriti attratti dalle stesse simpatie, pensosi degli stessi problemi.

I Blazius, i Vadius esistono; il loro grosso cugino Basile è ancora in piedi. Una volta – una volta sola – m’è accaduto di trovarmi colpita da quel miscuglio di insulti e facezie da caserma, di citazioni tronche o abilmente deformate per far dire alle nostre frasi la scempiaggine che non dicevano; argomenti capziosi, sostenuti da affermazioni al tempo stesso vaghe e abbastanza perentorie perché possa crederci il lettore rispettoso dei titoli accademici e che non ha né tempo né voglia di documentarsi personalmente su le fonti. Cose che caratterizzano un determinato genere, una determinata specie, fortunatamente assai rara. Quanta buona volontà, al contrario, da parte di tanti eruditi che, in un’epoca di specializzazione forsennata come la nostra, avrebbero potuto benissimo disdegnare in blocco qualsiasi tentativo di ricostruzione letteraria che rischiava di invadere il loro campicello… Moltissimi di loro spontaneamente hanno voluto disturbarsi per rettificare una frase, confermare un particolare, esporre una ipotesi, agevolare una ricerca ulteriore… Troppi, perché io possa esimermi dal rivolgere qui il mio ringraziamento amichevole a questi lettori benevoli: ogni libro ristampato deve qualcosa alle persone perbene che l’hanno letto.

Fare del proprio meglio. Rifare. Ritoccate impercettibilmente ancora questo ritocco. «Correggendo le mie opere, – diceva Yeats, – correggo me stesso».

Ieri, alla Villa, ho pensato alle mille e mille esistenze silenziose, furtive come quelle degli animali, inconsce come quelle delle piante: vagabondi dei tempi del Piranesi, saccheggiatori di ruderi, mendicanti, caprai, contadini che hanno preso alloggio alla meglio in un angolo di rifiuti, che si sono succeduti qui tra Adriano e noi.

Al termine d’un oliveto, G. ed io ci siamo trovate in faccia al giaciglio di vimini d’un pastore, in un corridoio antico sgombrato a metà: il suo attaccapanni di fortuna conficcato tra due blocchi di cemento romano; le ceneri ancora tiepide del suo focherello. Una sensazione di umile intimità, un poco analoga a quella che si prova al Louvre, dopo la chiusura, quando in mezzo alle statue si aprono le brande dei custodi.

[1958. Nulla da cambiare alle righe che precedono. L’attaccapanni del pastore, se non il suo giaciglio, è ancora là; G. ed io abbiamo sostato su l’erba di Tempe, tra le violette, in quel momento sacro dell’anno in cui tutto ricomincia, ad onta delle minacce che l’uomo dei nostri giorni fa pesare in ogni luogo su se stesso. Ma la Villa ha subito un cambiamento insidioso; non completo, certo: non si altera così rapidamente un complesso che è stato dolcemente distrutto e creato dai secoli; ma per un errore raro in Italia, alle ricerche e alle opere di consolidamento necessarie si sono aggiunti pericolosi «abbellimenti»; sono stati tagliati alcuni ulivi per far posto a un parcheggio indiscreto e ad un chiosco-bar tipo parco d’esposizione: cose che fanno del Pecile, della sua nobile solitudine una piazza della stazione. Una fontana di cemento disseta i passanti attraverso un inutile mascherone di stucco finto antico; un altro, ancor più inutile, adorna la parete della grande piscina, arricchita da una flottiglia di anatre; sono state copiate, anch’esse in stucco, statue da giardino greco- romane piuttosto banali, scelte tra reperti di scavi recenti: non meritavano né questo onore né questo disdoro. Sono copie, rifatte in un materiale volgare, gonfio, molle; collocate a caso su piedestalli danno al malinconico Canopo l’aspetto d’un angolo di Cinecittà, dove si è ricostruita per un film l’esistenza dei Cesari. Non c’è nulla di più fragile dell’equilibrio dei bei luoghi. Le nostre interpretazioni lasciano intatti persino i testi, essi sopravvivono ai nostri commenti; ma il minimo restauro imprudente inflitto alle pietre, una strada asfaltata che contamina un campo dove da secoli l’erba spuntava in pace creano l’irreparabile. La bellezza si allontana; l’autenticità pure].

Luoghi dove si è scelto di vivere, residenze invisibili che ci si è costruite a riparo del tempo. Ho abitato Tivoli, ci morirò forse, come Adriano nell’Isola di Achille.

No. Ho rivisitato la Villa ancora una volta; i suoi padiglioni fatti per l’intimità e la quiete, le sue vestigia d’un lusso senza fasto, il meno imperiale che fosse possibile, da ricco conoscitore che ha cercato di unire i piaceri dell’arte alla pace dei campi; al Pantheon, ho cercato il punto esatto dove si posò una macchia di sole un mattino, il 21 aprile; lungo i corridoi del Mausoleo, ho ripercorso il cammino funebre seguito tante volte da Cabria, da Celere e da Diotimo, gli amici degli ultimi giorni.

Ma non sento più la presenza immediata di quegli esseri, l’attualità di quei fatti; mi restano vicini ma ormai sono superati, né più né meno come i ricordi della mia esistenza. I nostri rapporti con gli altri non hanno che una durata; quando si è ottenuta la soddisfazione, si è appresa la lezione, reso il servigio, compiuta l’opera, cessano; quel che ero capace di dire è stato detto; quello che potevo apprendere è stato appreso.

Occupiamoci ora di altri lavori.

tratto da: Marguerite Yourcenar, MEMORIE DI ADRIANO, seguite dai TACCUINI DI APPUNTI, Traduzione di Lidia Storoni Mazzolani, Prima edizione di “Memoires d’Hadrien” 1951, Librairie Plon,Paris 1963 e 1981 Giulio Einaudi editore s.p.a., Torino